|

|

|

|

|

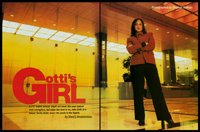

Gotti's Girl |

|

|

||

|

Call her the anti-Ally McBeal. Sarita Kedia, the criminal defense attorney her client (and reputed mob boss) John Gotti, Jr. considers his "angel," wouldn't be caught dead wearing a short skirt to court. The petite 28-year-old, born in Bombay and raised in Ruston, Louisiana, doesn't wear dresses, period. At least not while maneuvering around New York City's imposing halls of justice. Whether she's defending the alleged Mafia figure or a 16-year-old accused of slaying his best friend, her attire is a modest pantsuit. "A woman in this field has it tough enough when everyone presumes you're somebody's secretary or assistant." After just a few moments in the company of this woman whose 5'2" frame projects both fierceness and fragility, you sense that even if she were caught like Marilyn Monroe on that infamous airshaft, Kedia would emerge with her dignity fully intact. Yes, she's poised, superintelligent, and unafraid to express an opinion. What successful lawyer isn't? But few exude that intangible je ne sais quoi: presence. In the words of one of her two co-counsels on the Gotti case, Bruce Cutler, "Sarita is unflappable." The burly, white-haired Cutler, who, unlike Kedia, looks the image of a grizzled mob lawyer, continues, "I can't imagine the case without her. She's done so much of the heavy lifting: filing the motions, making court appearances, and handling the prosecutors and the press. Working with her has been a calming influence and an educational experience." Jerry Shargel, Kedia's boss and one of the country's top criminal lawyers, adds, "During the Gotti litigation I was also working on a death penalty trial. So I'd count on Sarita's encyclopedic knowledge of the facts; she knew all the subtle nuances of the case even better than the prosecutors." That's high praise for someone who was still completing her education just five years ago. Kedia escaped from the Southern Baptist town of Ruston (population 25,000) the second it was possible, attending a summer program at Harvard for bright precollege students, then earning a B.S.E. in business from Wharton and a law degree from New Orleans' Tulane University. Now her resume boasts a stint championing Gotti, the man she calls, "the son of the most infamous mobster since Al Capone." Her client, a self-described Long Island "businessman" and son of indicted crime boss John Gotti, Sr. serving a life sentence since 1992 for murder and assorted other wise guy acts, was indicted in January 1998 on counts of federal racketeering, extortion, loan sharking, beating and robbing a drug dealer, and other crimes associated with allegedly replacing his father as head of the Gambino crime family. Urged on by his lawyers, 35-year-old Gotti, Jr., accepted a plea bargain this April on the eve of his scheduled trial. Junior admitted to four acts of racketeering, but did not acknowledge being a mob family head. Kedia serenely accepts her share of the kudos for brokering this deal that will put her client behind bars for a maximum of five years and ten months. (Sentencing is set for July.) If he had been found guilty by a jury, Gotti's sentence could have been up to 20 years. "The government was doing to him what they did to his father, and it was my job to help keep that from happening," explains Kedia. "I mean, here's a man who's been hounded relentlessly by the Feds for 12 years, his every conversation taped. He starts a business, the Government subpoenas his records and questions all his employees. All this and he's never been convicted of a crime! He serves his time now, and hopefully he'll be allowed to lead a normal life when he's released from jail." This fervent defense of Gotti, Jr. is uttered three Sundays after the plea bargain. Kedia, relaxing in the sunny, one-bedroom Upper West Side apartment is sporting-yes! a pantsuit, small diamond studs, manicured nails, and a full face of makeup. Her gleaming black hair looks like the product of 100 nightly brush strokes. She sips water and leafs through a large binder of news clippings on her involvement in the Gotti case. Kedia recalls Gotti's initial reluctance to accept Shargel's word that his young female associate had the cojones to try a case of such magnitude. "For the first two to three months I knew him, John was polite to me but very standoffish," Kedia explains. "I didn't take it personally. In his world, men deal with men in business situations. End of story. Yet even though I'd already worked on several cosa nostra cases, was writing all the legal briefs in his defense, and had visited him in jail at least once a week, whenever John called our office and the secretary asked if he'd like to speak to me, the answer would be, 'No. Put Jerry on the line.'" Inevitably, the same grit that enabled Kedia to hold down a full-time job at one Manhattan criminal law firm while relentlessly auditioning for full-time work with Shargel by doing whatever he'd throw her way ("For the two months it took Jerry to ask me aboard, I worked almost every night until two a.m."), finally made the wise guy wise up, seemingly overnight. The landmark day came in May, '98, at the White Plains, New York federal courthouse. Kedia wound up arguing not only in front of her reluctant client, his 19 codefendants, and their 22 lawyers, but also in front of the government prosecutors and the media. Under many watchful eyes, Kedia successfully convinced the judge to grant her a much-desired extension on motions that were due the next week. Along with the postponement, Kedia won something more precious: Gotti's respect. Kedia recalls, "Jerry took me aside and said, 'I might not be able to try the case, but John definitely wants you.'" "Here is someone, very young, from a different cultural background, a woman, very petite. Sarita says she's 5'2" but I wouldn't bet the farm on it!" Shargel explains. "And when she opens her mouth to express an opinion, men shut up and listen. That's how compelling she is. And that's what Gotti witnessed that day in court-her low-key but undeniable persuasive power." Although Kedia, like any criminal lawyer worth her six-figure fee, doesn't need to believe in her clients' innocence in order to fight for them ("Probably the one person I would have a hard time defending would be someone who held me up at gunpoint," she claims), she nonetheless believes in her star client's humanity. "My clients who are underworld figures treat me like a human being. It's my clients from other walks of life who are often ball-breakers, second-guessing my every move. But I never felt intimidated by John. I think of him as a completely pleasant man, someone I'd go out for coffee with." Although Kedia and Gotti don't talk much about the "family," they've had many conversations about the importance of family. "I've never met Gotti, Sr., but John, Jr., adores him. I think he looks to his father as a man's man, a warrior's warrior, tough not on his family, but on himself. He taught his son to fight for what he believes in and that family should stick together." Kedia understands those sentiments. Her family left India in 1971 because her father got a job opportunity as a visiting professor at Grambling State University in Louisiana. "You didn't have too many Indians in the Deep South. So we all stuck together, celebrating traditional Indian holidays and singing bhajans (devotional songs) at least once a month," explains Kedia. "And although it wasn't like black versus white in the Civil War, I felt like an outsider. I remember a little girl wasn't allowed to come to my slumber party because her family thought we'd do an 'Indian rain dance.'" Episodes like that were hurtful to Kedia, but she never let it bother her. "I came out of the womb fighting," she says. Her sister Kavita Erickson, 34, recalls how Kedia would use humor to deflect potential prejudice. "Before Sarita would bring a non-Indian friend home, she'd jokingly warn her, 'Look, my mom's not dressed like your mom. If she lives to be 100, she'll still only dress in a sari.'" Kedia's chameleonlike ability to sunnily adapt to any situation is rooted in her upbringing straddling parallel worlds. On one hand, she was exposed to all things American; on the other, her strict Indian parents didn't allow her to date or party. But from both cultures she received a strong mandate to achieve. Her mother, Sushila Kedia, who has two master's degrees and now teaches full-time, recalls proudly, "When she was five, she was doing algebra equations from her older sister's textbook." Erickson, that sister, adds, "We might not have imagined Sarita would wind up defending mobsters, but always knew she wouldn't stay in Louisiana. She didn't even attend law school graduation. She flew right to New York to start her career. Sarita always needed excitement." Kedia has found that excitement scoring a series of victories for Gotti. Her first win was getting Gotti, Jr. bail after he'd sweated out nine months in jail. The second was convincing the judge to turn down the prosecution's petition for an anonymous jury. (The government made this request because Gotti, Sr. had been accused of bribing jurors in at least three past trials.) The third was ironing out a plea deal that will have her client back out playing soccer with his four children while they are still young. Novelist Victoria Gotti ("I'll Be Watching You"), Junior's sister, has surged to the head of the Sarita fan club. Gotti not only calls Kedia "ferocious" and "a lioness," but she pays her brother's attorney the highest compliment a writer can make: "I'd like to model one of the characters, a female lawyer, in my next book after her." While Kedia doesn't want to become labeled as strictly a mob attorney, she's rapturous about the prospect of landing more high-profile criminal defendants who will keep her name in the news. "If Puff Daddy gets in trouble again, tell him to call me." She adds, "I love working for Jerry, but of course one day I want to have my own practice." And if a good percentage of her future clients are connected to the mob, so be it. Kedia asserts, "Anyone who sees issues in black and white-good guys and wise guys-is wrong. No matter what a person has done, he deserves a defense. And I'd love to be the one to give it to him."

| |

|

||